Our solutions are tailored to each client’s strategic business drivers, technologies, corporate structure, and culture.

Section 1603: Lessons for Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) recipients

The $26 billion Section 1603 program offers valuable lessons for GGRF recipients about how to leverage the tax credit opportunities available.

Between 2009 and 2018, the U.S. Department of the Treasury ran one of the largest renewable energy grant programs in recent history. That program – the $26 billion Section 1603 program – offers valuable lessons for Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF) recipients about how to leverage the tax credit opportunities available in the GGRF program to maximize private capital and community impact.

The $27 billion GGRF is unlike previous large federal investment programs:

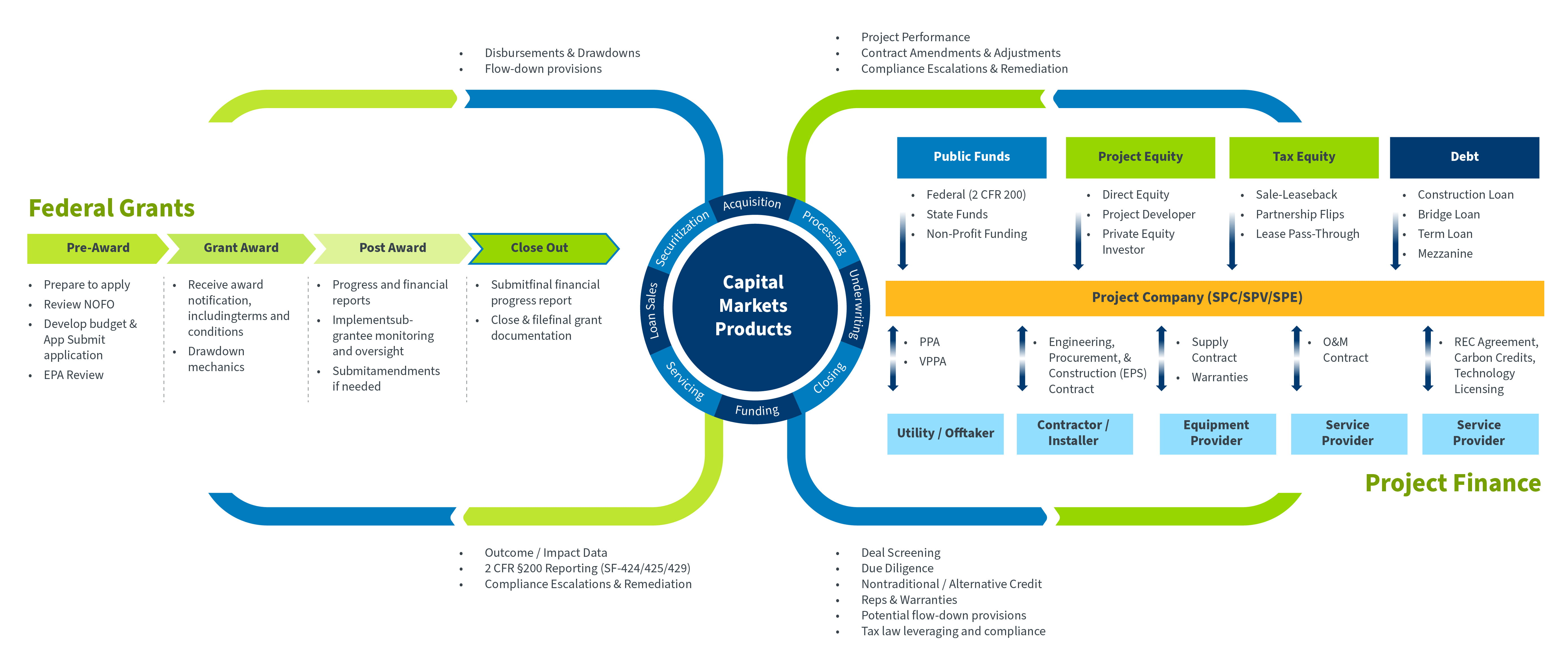

- A merging of three different financial taxonomies – the grants’ world, the capital markets’ world, and the world of project finance – with a goal to create durable investment nationally that will exist for years to come;

- The focus on low- to moderate-income households and communities (LIDACs) reflects an intentionality to deliver benefits to America’s most vulnerable populations and embed equity principles in every investment consideration; and

- The need to tap private sector finance and lever up the federal funds.

There is broad recognition that $27 billion is not nearly enough to decarbonize the economy of the United States, not when even the World Bank estimates the global “climate financing gap” to be $2.4 trillion annually by donor countries. This means that to maximize the effect of the GGRF, recipients and subrecipients will need to be thoughtful about how use of federal funds can attract private capital.

After the 2007-2008 global financial crisis, the Treasury Department launched a large, renewable energy program similar to the GGRF. The Section 1603 program was intended to leverage public sector investment to crowd in private capital and spur clean energy deployments nationwide. GGRF recipients and subrecipients are therefore able to benefit from the lessons learned and successful models from Section 1603 as they plan their own programs under all three GGRF sub-programs: the National Clean Investment Fund (NCIF), the Clean Communities Investment Accelerator (CCIA), and the Solar for All (SFA) programs.

CohnReznick advised dozens of project developers on hundreds of successful Section 1603 applications that represented billions of dollars in clean energy investment with a 20-year history working in renewable energy finance with hundreds of projects financed. We also advise numerous successful GGRF applicants, covering everything from federal grant applications to strategies for leveraging IRA tax credits and Direct Pay. Here we’ll share our insights on what made Section 1603 successful and how GGRF recipients can learn from – and optimize – the recent experiences from that similar program.

Section 1603, also known as “Direct Pay 1.0”

Beginning in 2007, the financial crisis triggered a macroeconomic shock that impacted a broad range of industries globally. In the U.S., renewable energy investing was one such sector. Investments in clean energy decreased significantly in 2008 and 2009 as the value of tax credits – such as the Production Tax Credit (PTC) and Investment Tax Credit (ITC), critical incentives for clean energy investing – plummeted to near-worthlessness when demand for debt capital contracted across almost all asset classes.

To jumpstart investments, Congress passed the $787 billion American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA or Recovery Act). The Recovery Act included a program which would kickstart the tax credit market by offering developers the option to receive a 30% cash grant in lieu of either the ITC or the PTC, for eligible energy projects put into service. That program – the Section 1603 Program – was managed by a team of federal finance and grant administrators at the U.S. Treasury Department in conjunction with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). Many now consider the Section 1603 program as “Direct Pay 1.0.”

The Section 1603 program achieved significant successes during the program’s existence, from 2009 through 2018:

- Developers collected $26.2 billion in cash payments

- Federal funds helped “crowd in” $67.9 billion of additional private finance

- Public and private investment funded 109,000 projects in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and four overseas territories

- Projects accounted for 34.6GW of clean energy installed capacity

- Projects generate 91.5 TWh of clean electricity – enough to power 8.5 million homes

Projects covered a dozen eligible clean energy technologies, including biomass, fuel cell, geothermal, hydropower, landfill gas, small- and large-scale wind, and solar. The projects also accounted for the creation or retention of thousands of jobs in the renewable energy sector prior to the sunset of the program in late 2018.

Section 1603 and the IRA’s Direct Pay

In August 2022, President Biden signed into law the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which includes a historic $783 billion package of investments, grants, and tax credit opportunities intended to accelerate America’s energy transition. The IRA introduced a broad menu of new tax credits beyond the traditional PTC and ITC, as well as two new funding mechanisms.

- Transferability – allows for-profit project developers to sell tax credits by transferring them to other taxpayers.

- Direct pay – a mechanism whereby nonprofit and a limited number of for-profit entities can monetize clean energy tax credits, many for the first time.

In terms of mechanics, direct pay shares many similarities with the Section 1603 program. Project developers under both programs receive incentives designed to encourage investments in clean energy projects. And under both programs, eligible taxpayers are entitled to receive a post-deployment cash refund in lieu of certain tax credits for directly owning eligible project assets once they are fully complete and operational. Both the IRS and the U.S. Treasury will play a role in recording the credits and with potential recapture in the event of default. And in the case of both programs, those cash payments provide an additional source of funding to recipients.

However, there are important points of distinction between the current IRA programs and the now-expired ARRA grant program. Under Section 1603 the cash payments were available to for-profit project developers, up to 30% of the eligible versus taxable cost basis of a project. Local governments, state governments, and other nonprofit entities could not qualify because they do not typically pay federal taxes. Additionally, at the time for ARRA, there was no statutory exception allowing tax-exempt use. However, the IRA has changed the game. Under the Direct Pay provision of the IRA, cash payments for tax credits are expanded to a broader community of entities including nonprofits, state and local governments, Tribal entities, publicly owned utilities, and rural electric cooperatives. In the case of the newer Direct Pay program, these cash proceeds can be used to help enhance some projects and make them more credit-worthy by bringing more and less expensive debt capital to the table. This will allow some marginal projects – ones that have been hardest to fund, often the ones that could help the most vulnerable households – to achieve the required rates of return to make them attractive to investors.

Section 1603 lessons learned for GGRF recipients

Under Direct Pay, tax-exempt entities will be able to monetize clean energy tax credits for the first time. These payments are going to flow into what is already a crowded investment landscape. Separately, the GGRF will be pushing $27 billion in federal grants to dozens of nonprofit, state, local, and Tribal government entities. These entities will also be sourcing private capital from a variety of providers, which could include private equity, large financial institutions, community development financial institutions (CDFIs), credit unions, and impact investors, to name just a few. Braiding all these federal and non-federal funding streams – while maintaining traceability and auditability across the federal and non-federal shares – will create complex internal control and reporting challenges.

Traceability across funding streams

One of the challenges under Section 1603 was the complexity of the capital stack for proposed projects. Developers would structure complex entities in the form of Special Purpose Companies (SPV, SPC, SPE), and the expected Treasury payment – up to 30% of the taxable cost basis – was factored in during the project origination phase to help adjust the capital stack and lead to more advantageous lending terms. In the GGRF, however, you will have grant monies flowing into revolving lending vehicles, with additional potential flows of funds from sources such as Direct Pay refunds, among others. This means that GGRF entities will need to pay close attention to tracking the deployment and ultimate disposition of those funds. This means careful design of internal controls, reporting, data structures, system design, and ensuring these requirements are built into all counterparty legal and loan agreements.

Rewarding performance versus investment over the estimated useful life

Various Inspector General reports on the Section 1603 program noted that there was an over-emphasis on the upfront investment, that the grant payments tended to reward investment versus long-term performance. Generally, the use of PTCs leads to more efficient outcomes because better-performing projects earn more PTCs over time (whereas the ITC is simply representative of front-end investment). PTCs therefore encourage developers to minimize installed project costs and focus on maximizing performance over time. Most GGRF projects will have estimated useful lives – and be expected to be delivering benefits – over long-term time-horizons of 20, 25, even 30 years, and beyond. GGRF entities should pay close attention to the mechanics of, and terms embedded in project operations and maintenance (O&M) agreements for funded projects. Although the EPA may only need 2 CFR 200 compliant performance reporting for 5-7 years, since these investments use federal funds, then Inspectors General will have wide berth to track performance of the federal share over the entirety of a project’s estimated useful life. GGRF entities need to plan their compliance and oversight functions accordingly.

Outcomes quantification and gold-plating

The Section 1603 program faced repeated questioning from Inspectors General as well as Congressional committees about outcomes, especially metrics around:

- Number of clean energy jobs created;

- Accusations of gold-plating and performance issues; and

- Compliance.

Despite the Section 1603 program using the NREL Jobs and Economic Development Impact (JEDI) Models, it was hard to quantify the number of jobs created by the program. Developers were directed to self-report these numbers without any context around methodologies, whether they were permanent or transient roles, whether they were actually created anew or simply retained, etc. GGRF recipients should start working on these approaches now, such as working with statewide labor and workforce development agencies, to adapt models and ensure they will collect the right data to inform those models. And because the ITC focuses on investment, there is a risk that developers could “gold-plate” projects by adding equipment that does not necessarily contribute to more efficient performance. This will be especially true for subsidized multifamily housing, where there may not be individual household electric bills and developers may suggest amenities such as upgraded fitness facilities, laundry facilities, lobbies, or doormen as alternative benefits. GGRF entities need to be thoughtful in defining what they will accept as “delivered benefits” before making awards.

Compliance requirements – BABA, Davis-Bacon, NEPA

The Section 1603 program was exempted from requirements such as Davis-Bacon (prevailing wage), Build America Buy America Act (BABA), and the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA). However, the EPA has already indicated that the GGRF will be subject to statutory requirements such as both Davis-Bacon and BABA. Given the environmental impact of these projects, there is a likelihood that NEPA considerations could come into play down the line. As projects get underway, there are a host of other statutes that may come into play as construction breaks ground. Some might include, but not be limited to, the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the Clean Air Act (CAA), the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA), and the newly enacted Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), among others. Recipients should begin creating checklists of relevant statutes and formulating approaches to engage with stakeholders and address concerns before projects break ground and work stoppages are ordered when situations arise.

In conclusion

GGRF recipients can learn from the challenges of the Section 1603 program by focusing on compliance with federal requirements and maintaining detailed reporting to track outcomes. By utilizing the lessons learned from the 1603 program, GGRF recipients can maximize the impact of federal funds and provide a lasting community impact.

Contact

Let’s start a conversation about your company’s strategic goals and vision for the future.

Please fill all required fields*

Please verify your information and check to see if all require fields have been filled in.

Related services

Any advice contained in this communication, including attachments and enclosures, is not intended as a thorough, in-depth analysis of specific issues. Nor is it sufficient to avoid tax-related penalties. This has been prepared for information purposes and general guidance only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice specific to, among other things, your individual facts, circumstances and jurisdiction. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and CohnReznick, its partners, employees and agents accept no liability, and disclaim all responsibility, for the consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it.